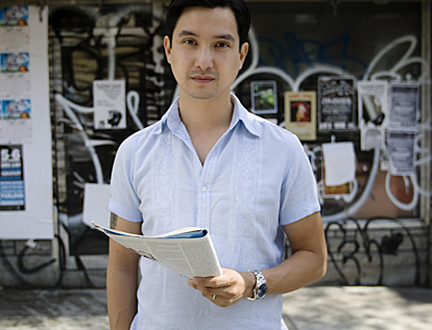

Be Here Now

By Miguel Syjuco

We have commissioned a new piece of writing from fifty leading authors on the theme of 'Elsewhere' - read on for Miguel Syjuco's contribution.

It’s exciting to get to know your new kitchen and its appliances.

The white promise of the stove-top.

A microwave with unblistered buttons and walls still spatterless.

The fridge unburdened, free of the steeped scents and mysterious residue of condiments collected in the ridges of the shelves. Swing open its door and it’s as if the bulb was always on, like a welcoming porch light; the half-emptied boxes of kung pao chicken, spring rolls, and chow mein echo those larger ones labelled, stacked, and half unpacked in the bedroom, the hallway, the open-concept living room.

Jenna hangs a painting on a wall. Jenna asks me if it’s straight. Jenna has a hard time figuring out the latch before opening the window. In rushes night air and the plaintiveness of a guitar being played by a distant neighbour. Something sets off the motion-detector light in the backyard next door and Jenna is beautiful in its illumination. Still hungry? she asks me. Just looking at my new fridge, I tell her. I close the door and the kitchen is dark and unfamiliar again. Ow, fuck, I stubbed my toe, I say to Jenna, and she puts down the tinkling box of light bulbs and comes to me to wrap her arms around my neck and quietly whisper thank you for doing this.

We spent yesterday afternoon writing my father’s name on labels and sewing them onto his clothes. We rushed to check out from our motel and deliver his suitcase before visiting hours ended at the residence. He just stared out of the window in his room, pretending he’d forgotten who we are, refusing to acknowledge us when we spoke to him. Jenna and I drove the five hours home squinting into the descending sun. She rattled off rationalisations for me, as if singing to music. I looked at her often, to try to remember always how the sun lit up her green eyes. On the way, we got lost. We argued, my map-reading skills stubborn against her knack for recognising landmarks. Even when we accidentally found our street, we couldn’t distinguish our bungalow from the others. We’d forgotten what number it was. In the end, we knew our home only because it was the only one that was completely dark.

Jenna asks me if I want to smoke a joint and explore the neighbourhood. I tell her I’m too exhausted for anything but hitting the sack. The only thing more tiring than a Saturday spent packing is a Saturday spent unpacking. Her job at the conservatory starts Monday week. In the alcove off the living room, her bag of books and supplies sits beside her desk, like a schoolboy sulking over the last days of summer. I stand over the desk and fire up my laptop. Hey, I call out, unprotected wi-fi from next door! Jenna peeks out from the bathroom and pulls her toothbrush from her mouth to smile widely. She clears her pile of clothes from the office chair and wheels it over. There, she says proudly, make yourself at home. She tousles my hair. She tells me she put in the mattress topper and bed sheets. No more sleeping bags, she says. Memory foam, she says, trying to entice me. Costco’s best, she says. I’m not yet tired, I reply, I’ll be along soon, it’s not even eleven. She looks at me as if I’m hiding something but decides against saying anything. She kisses me on the head and retrieves her stack of bridal magazines from her desk. She closes the bedroom door behind her.

It’s good to be home, even if home is unfamiliar. Jenna had done all the packing while I was away shooting. All last month, each time we Skyped – her bedtime, my dawn – I saw our apartment progressively stripped of its familiar Ikea items, cardboard boxes slowly accumulating behind my fiancée. Then there was her frantic call while I was covering a pro-democracy rally – the movers hadn’t shown up, the new tenants were moving in the following morning. Then the sad text messages all weekend – she was driving from our city of five years, en route to somewhere entirely new to us both. Those brief moments of connectivity with Jenna grounded me, and for the first time in my life I felt the pull between where I was and wasn’t. Somewhere beyond my thrill of being so alive in a place of everyday death, beyond the adrenaline, beyond the confidence of a noble cause, the home Jenna and I had built was being dismantled for lives moving forward and I wasn’t there to be part of it. Never had I understood the soldiers and aid workers better, even if we were opposites, they impatient to change things while I rushed to capture things before they could be changed. The photos Jenna had emailed of the houses we could choose as ours, their bathrooms brightened by flash and a tantalising fragment of Jenna chanced in the mirror, served to both highlight the bloodshed and make it more unreal and therefore more bearable in the images I was preparing on my laptop to send to the wire service. Even though I had been on those streets only hours before, the quotidian horrors – the toddler with feet blown off, the stacked bodies almost made anonymous by ubiquity but for the anguished embrace of relatives – all felt as if from some Hollywood flick recently seen at the theatre. We all have ways of coping, of sublimating or acting out, but Jenna’s constant activity in the margins of my days and nights simultaneously soothed me and made me fear for our lives.

I check my email. I’m relieved and disappointed there’s nothing. I browse through some of my photos that made front pages.

A soldier on his knees defusing an IED on the roadside outside a school, the swings in the background moving in the wind.

A row of local soldiers facing off with angry residents who point and curse at them.

A group of boys hiding behind mothers and sisters dressed in niqabs, the women’s eyes expressive against the expanse of black cloth.

I showed those pictures to Jenna over dinner tonight. She said she was proud me. I’m proud, too, though I often fight the feeling I’ve grown into a vulture. Colleagues tell me I shouldn’t think too much, but that strikes me as wrong. It’s our responsibility to think, and it’s our victory to bear it. I do take comfort in the old idea that we must witness suffering so that it may not be repeated. But callousness and naivety make strange bedfellows.

I know won’t be able to sleep. I know by experience that it takes at least a week to negotiate the limbo between this world and the one I’ve left behind. Usually, as now, I say it’s jet lag. Every day we fool ourselves, though some of us are more deserving of illusions.

I surf the net. I check my email. I’m like a smoker jonesing for a cig, the online connections like a rush of nicotine after a flight or a meeting. The headlines on the news sites are the same variations – a bombing in the Middle East, a school shooting in the Midwest, an earthquake in northern China – recurrences now too foreign and too familiar to me. To us.

Twitter is a burst of noise that I can’t negotiate right now.

The Craigslist classifieds offer free stuff. Crap I don’t need, crap I want but don’t have space for.

Bamboo blinds.

Broken dishwasher.

Plaid couch.

Tail lights for a Jetta.

Air hockey table with only one paddle.

It’s a shame Jenna won’t appreciate a stuffed moose head in our living room.

Wood pallets.

A boulder? There’s even a picture of it. It’s round.

I have a photograph somewhere of myself as a boy standing with my grandfather on a similar rock, taken in a valley in the Rockies of eastern British Columbia. I was too young to form an indelible memory of that time, though the picture and my parents’ stories have convinced me I remember it well. I can’t recall touching my grandfather in his coffin a couple of years after that picture was taken, though my parents tell me I did; but I have somehow retained, or maybe formed, a memory of standing on that rock, holding my grandpa’s hand. I know what his hand felt like at that moment, its skin dry and rough like a corkboard, its flesh soft beneath as if already falling away from his bones. I remember visiting the site of the internment camp where he and my father had lived for four years. I’m not sure if my memories are of that very day or of my parents’ recounting of it, but I know I walked in what was by then an anonymous field along an unremarkable road. I can close my eyes and see the boarded up building where my grandmother stood outside and told me it was there where the guards would look at her with with anger and disappointment that she, a white woman, had come to visit the enemy. I google the name of the village and find its official website, hoping for pictures to fill those gaps in my memory. I click on a link: “History”.

The 1890s, gold rush.

1901, Slocan becomes a city.

1921, Slocan Lake freezes over.

1947, Mrs. E.D. Popoff elected first woman mayor in BC.

1958, Slocan becomes a village.

1989, New #6 highway completed.

2000, Springer Creek RV park opens.

No mention, no pictures, of the camp where my grandfather spent his prime, my father his adolescence.

On Facebook, I have four new friend requests. I don’t know any of them. Monica Garcia has posted a picture on my wall. Who is Monica Garcia? Scrolling down her profile, I really don’t remember her. Her profile pic is of her smiling, leaning into some guy who has his arms around her. There’s an ostentatious pride in such photos of sweet pairs, showing off how much they believe in love. What I see is implied incompleteness, tacit neediness. I accept Monica’s request, so that I can slideshow through her photos:

Monica in front of the fake Eiffel Tower in Vegas.

Monica bicycling.

Monica with a four friends at a party, each dressed as a Spice Girl.

Monica with family around a Christmas tree, everyone trying to outdo the others with hideous yuletide sweaters.

Monica carrying her infant nephew, gazing at him as if he was cute.

What is she trying to say by sharing such pictures publicly?

Look, everyone, I’m happy!

Look, folks, life has treated me well!

Could that really be true if you need to declare it? Is it less true if you need to memorialise it before it’s gone? They’re perfect pictures from an imperfect life. Isn’t that the truth? Every time we pose for a camera we’re making a wish without knowing it.

I click on what she’s posted. It’s an old photo of me. I look so young. I always posed that way – brazen, insouciant, like someone who is asking to be punched but hasn’t found any takers yet. I even remember that party. This time of year many summers ago, home from my freshman year.

It wasn’t the first night I’d kissed Charmane, but it was the first night she let me put my hand up her dress and a finger inside her.

I remember that dress, how, after we’d first made love weeks later, I’d picked it up off the floor. The tag read “FCUK” and I thought, how fitting.

I remember how she held me on the back of my motorcycle, how she squealed when I popped a wheelie, how I killed the engine and coasted up to her house with my lights off, and how she took off her shoes and tiptoed barefoot so as not to wake her dad.

I remember her slender feet.

How wonderful it is to be able to say those words, without regret: I remember.

On the highway home, I made myself speed beyond my comfort zone, the thrill multiplying everything about that evening, to the point that I arrived at our driveway with my hands and knees trembling. I remember laughing at my frailty.

I remember calling her after sneaking into my own room, to tell her I arrived safely.

With memories like those, how could we have given up on each other?

I look at the motorcycles on Craigslist. I look at the personals, the Missed Connections. I look at listings for cars, houses, collectibles, vacation rentals. I check my email. On Facebook, I find Charmane’s profile. Access is restricted to only her friends. I don’t want to write her. Maybe I’m afraid of the decay that years will always divulge. I look up from trawling for whatever it is I’m searching for. It’s nearly three. Fuck. The tea kettle and chamomile are still packed, so I go to PornTube and masturbate. I wipe myself off and check my email. I force myself away from the desk and stand outside on the uneven paving stones leading to our garage. The night is peaceful with its usual racket. I walk on our lawn. Overhead, an airplane passes sonorously, but I can’t see it. I feel my way to the bedroom. Jenna snores quietly. Her face is lined in silver from the security floodlight in the neighbour’s backyard that is on, then suddenly off.

The next day, Jenna lets me sleep until noon. We spend the day arranging furniture, emptying boxes, and filling rooms with framed paintings and prints, bric-a-brac, and boxes now useless. Before we know it, the day is over, and Jenna is lying on her stomach in bed paging through a magazine for wedding dresses. She looks up at me and pats the space on the bed beside her. Come on, she says, closing her magazine. Let’s look at this one, she says, opening a magazine for wedding venues. She flips to the pages she’s marked with post-its, displaying them like they were centrefold models:

A village outside Avignon.

An historical hotel in New Hampshire.

A beach in Bali.

A loft with views of the New York City skyline.

I smile. I have work to do, I tell her, on the computer. I promise I’ll come to bed shortly.

I check my email. I look a couple of cartoon sites. One has an old man telling his grandson, “When you get as old and gassy as me, the best investment you can make is a dog and a leather armchair.” I look for chrome accessories for a Vespa I don’t own. On Facebook, I read the posts, statuses, and conversations from my network:

Stella is tired from work.

Kenza is now in a relationship with Phil.

Stephanie thinks sanity is overrated.

Ditto says the France-Algeria match was colonial comeuppance.

Valdes says: “Heatwave in NYC = God’s armpit.” To which Cach replies: “Sounds like New Jersey.”

Gelareh posted photos of her new vintage outfit.

Someone I don’t know, Caroline, posted photos of herself at a beach wedding.

Maria has put on something like 50 pounds since I last saw her in high school. But she looks happier than ever.

On Fran’s wall, Elmer has posted a picture. It’s of a framed photo of Fran placed in front of a coffin flanked by flowers. I click on it. There are 45 comments below: “RIP Fran!” “You were too sweet for this world, Frannie.” “A shooting star, baby!” The posts are dated last year. I click on Fran’s profile. Her main pic is her smiling while windsurfing. Her basic info says she’s interested in men, and is looking for friendship, dating, a relationship, random play, whatever I can get, networking. Also listed are her past employment and current job, the schools she attended, her favourite books and bands, the quotes she most loves. Loved. She has 4,200 friends. Had. Has. On her wall, one of them has posted, “Hi Fran, just saying hi wherever u r. We miss you. Hope ur dancing n having fun.”

I wonder how long her page will remain, how many months or years servers will keep our profiles, even when we’re already somewhere else. I hope they outlast even memory.

I watch old music videos on YouTube. Journey, Queen, the Smiths. I compare reviews on Weber and Broil King barbecues.

On Craigslist, I look at the personals. Casual Encounters:

White bi-top seeks MFM w/ cuck couple.

BBC bull with 9-inch curve for BBW.

Attractive BF & GF visiting town ISO similar for same room sex or, should chemistry be right, soft swap.

I wonder how fine is the line between loneliness and lust?

I read the Missed Connections personals.

Says one: “Hot concert security guard, sorry I laughed when you got reprimanded for letting me pee behind the equipment van.”

Says another: “You – Sexy carpenter in ripped-jeans, smokin-ass Chevy Colorado, Joe Boxers. I could see your pecs squeezing out off your shirt. Me – 35-year-old housewife looking for a little something-something on the side. Call me. We can cuddle and watch ‘True Blood’ together.”

I lie down beside Jenna and watch her sleeping. Her eyelids flicker with REM sleep. She smiles at something. She giggles. Where has she gone that makes her so happy? How can I get there?

Each following day passes like its predecessor:

Unpacking.

Hanging.

Arranging.

Eating.

Talking.

Avoiding discussing the wedding plans, pretending I’m a typical guy.

Sitting at the desk, mimicking work until Jenna goes to sleep.

Two days ago, the email arrived. My editor outlined my new assignment. I deleted it.

This morning, Jenna cooked breakfast for both of us for the first time since I got back. Happy Sunday, she declared. She stood at my bedside with breakfast on a tray. I said I was still too jet-lagged and I turned my back on her. I heard plates and glasses crash in the kitchen sink. We didn’t talk all day. I slipped out to the garage and unboxed tools, hardware, cans of oil, antifreeze, solvents, paint. Through the window I could watch Jenna in our bedroom, arranging the closet into sections, for foldable shirts, hanging shirts, trousers, underwear.

The final box in the garage was mis-labelled. It shouldn’t have been put here. I sit in front of it and unpack things one by one. My old pencil-case. Comics. GI Joe figures. Photo albums. Soccer trophies. I hold in my hand the daruma doll my father bought me on my first trip to his ancestral prefecture. It’s as good as new, its red and gold papier-maché still vibrant. I place it on the floor and push it. It rolls back and forth on its heavy bottom, bowing repeatedly. One eye is blank white space, while the other is a yellow circle I drew in crayon long ago. I remember rain falling outside the market, my father explaining that darumas are symbols of good fortune and strong determination. People paint in one eye when they set out to do something, he said, and they paint in the other when that something is done. I look at the painted eye. I don’t remember what goal I’d set out to pursue. I search the crayons in my pencil case until I find a blue one. Very slowly, I colour over the yellow.

Jenna calls my name from the back door. Where are you? she says. I finish redoing the eye. It’s now green. Jenna calls my name. I step out from the garage. There you are, she says. She smiles. Where’ve you been, she says, I’ve been wondering why you weren’t with me.

Copyright © 2010, Miguel Syjuco. All rights reserved.

Supported through the Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund.

Find Events

Latest News

Celebrating the 2024 Book Festival

Celebrating the 2024 Book Festival