More articles Friday 23 August 2013 12:45pm

Guardian editor speaks out at Book Festival

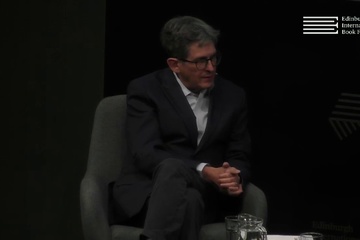

“I’m surprised it took them so long to ring me up” – Alan Rusbridger said in an event this afternoon at the Edinburgh International Book Festival.

In an event ostensibly about his self-imposed challenge to learn one of the most complex pieces of piano music imaginable, Alan Rusbridger, editor of The Guardian newspaper, also discussed his views on the role of journalists in the modern world, and the increasing threat imposed upon them by government censorship and political timidity.

Fellow journalist, Ruth Wishart, who chaired the discussion, opened proceedings by acknowledging the elephant in the room: that two hours previously the UK police announced they would be launching a criminal investigation based on information gleaned from the electronic devices seized from David Miranda, the partner of a Guardian journalist, during his detention at Heathrow airport. Who would be the subject of the criminal investigation had yet to be announced and Wishart’s comment that Book Festival staff had “both doors covered” in case the “plods” burst in was met with both laughter and a collective sigh of relief: this was something that Rusbridger could, and would, be talking about.

“The most bizarre journalistic moment of my life” was how Rusbridger described having to stand in his building’s basement and watch his staff destroy Guardian laptops containing ‘sensitive data’, under the eye of officials from GCHQ. He spoke of “two worlds colliding…the world of security and the world of journalism” and of their irreconcilable priorities in a world changing as quickly as ours today.

The problem Rusbridger identified was a lack of debate – only four MPs so far, for example, have raised the issue of David Miranda’s very questionable detention at Heathrow, and only 3 of them critically. “We’re dealing with a ‘just leave it to us, just trust us’ culture” he said, in respect of the actions of GCHQ and their American opposite-number the NSA, and questioned the legitimacy of allowing a tiny coterie of “technocrats” to set policy on what information should be publicly available and what should be held back for reasons of national security.

Wishart then brought the conversation around to whistleblowers: a subject upon which Rusbridger is almost uniquely qualified to comment. He described Bradley Manning’s recent sentence of 35 years for his role in the Wikileaks scandal “enormously draconian” and “so obviously a deterrent to other whistleblowers”. Rusbridger also talked of the “big philosophical question” Edward Snowdon must have wrestled with before flagging up the NSA’s unprecedented access to the private lives of American citizens, and, in response to an audience member’s comment that Snowden shouldn’t have said anything as he was legally bound not to, that “often you only get to [important revelations] by people, in defiance of the contract they’ve signed, in defiance of the law, telling you stuff.”

“We need to know what the bargain is” said Rusbridger in closing, meaning there needs to be more transparency in what we are gaining in terms of safety and what we are losing in terms of privacy when we let governments into our online lives. It is an ideal that seems more utopian as time progresses, and something that looks likely to occupy more and more of Rusbridger’s thoughts in the immediate future, as British authorities review their coping strategies for journalists, terrorists and the rest of us, in light of their newfound ubiquity of surveillance.

Find Events

Latest News

Celebrating the 2024 Book Festival

Celebrating the 2024 Book Festival