Sullivan's Ashes

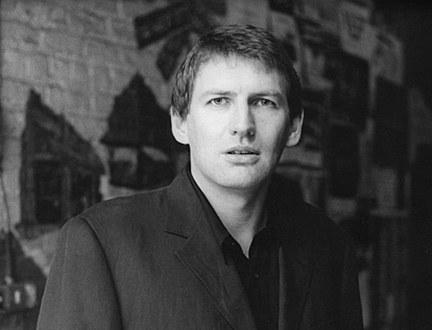

By Alan Warner

We have commissioned a new piece of writing from fifty leading authors on the theme of 'Elsewhere' - read on for Alan Warner's contribution.

Myself, Cousin John, Sullivan’s third wife Aileen and the sergeant all sat together in the police station at Tobermory. We read once more the photocopied clause in Sullivan’s will:

I wish for no funeral service but to be cremated privately and then for my ashes to be spread from the specific silver urn, by a semi-naked and beautiful woman, galloping a white horse across the sands of Calgary Bay, Isle of Mull – irrespective of expense, inclement weather and the challenge of finding a beautiful woman on Mull.

‘Aye. He had to get that last wee dig in, right to the bitter end,’ said Aileen – the only native among us.

We looked to the sergeant, a pleasant and practical man. But new to the job.

‘It’s no an urn. It’s his bashed up old champagne bucket from The Grand in Brighton, 'Cousin John revealed.

‘Yes,’ said Aileen. ‘And if it hadn’t been full quite so often, he might have had something to leave me. Us.’

‘But it said here he’s leaving you the bucket.’ John rustled the pages to quote it.

Aileen gave Cousin John a hard look. ‘I’ll use it too, once I’m rid of his leftovers.’

Practical as ever, the sergeant asked, ‘How are you to keep the ashes in a champagne bucket, with the great probability of a howling gale?’

Quickly, Cousin John said, ‘I was thinking a good dose of yon kitchen clingfilm stuff over the top, and the lassie can pierce it with her long fingernails?’

The sergeant and I both nodded, though we all felt Cousin John was getting a bit ahead of the game. He went on, ‘And we’ll need Doc Fraser standing by. To treat the lassie for frostbite. Best if we get a healthy young lassie. One of them strip-o-grams. They stand up best to the cold. I respect those lassies.’

Aileen said, ‘I don’t want the doctor there and I doubt he’ll attend. Sullivan never invited him back up to the poker evening, not when he got the house off him but after he stopped prescribing those sleeping pills.’

‘So you intend to proceed?’

‘This is what we wanted to ask, Sergeant. From a legal point of view. The possible ramifications?’

‘Round here, that could depend on exactly how…’ he flicked the page and read aloud, ‘ “semi-naked” any young lady actually is.’

‘Topless,’ Cousin John demanded.

I said, ‘On Mull, semi-naked is a bikini.’

‘A bikini doesn’t break any law. Topless might be indecent exposure. It’s certainly exposure, in this climate.’

Aileen took another Dunhill out her pack and told us, a bit nostalgically, ‘On Mull, semi-naked is a skirt above the knee. Can I smoke in here?’

‘I’m afraid not,’ said the policeman.

‘Couldn’t you lock me in one of your cells, Sarge? I’d even close the peephole.’

I gave Aileen a look. She wasn’t a day under fifty-five but still well-preserved and hopelessly flirty. The sergeant ignored her. What can you say about Aileen? Her life was like all those Dolly Parton songs. Or maybe just one: Down From Dover.

I said, ‘So we have a week or so.’

Cousin John pondered, ‘Unless we wait to watch the weather. For the sake of the beautiful lassie on the horse?’

Aileen erupted. ‘I’m no having Sullivan’s ashes waiting up in that house. They’d crawl out and make for the drinks cabinet. Why the hell couldn’t he have them scattered off the South Downs in a gentle English breeze?’

The sergeant looked troubled now. He stood. ‘I might need to phone Edinburgh about all this. ’Then he thought aloud to himself. ‘But what department?’

‘Another thing.’ The cousin held up a pointed finger – and he was a farmer. ‘There’s no a white horse on this whole island.’

‘Oh good god,’ Aileen groaned. ‘Use a Highland cow.’

‘It’ll no gallop,’ the cousin shot back, in a voice revealing too much experience in such a matter.

Aileen, Cousin John and I drove back up the tiered roads to Sullivan’s modern holiday bungalow, high above the bay. In the disused connecting garage sat the scandalous American pool table.

The house had been won off Sullivan by Doc Fraser in a two day poker marathon years before, to legally pass to the doctor at the time of Sullivan’s death. The doc had already been up to measure for new carpets.

Plumpton, the fat cat – named after the Sussex racecourse – sat by a bowl on the kitchen floor. He’d brought round some semi-feral acquaintances for a meal. Four of the beggars. They all sat, turning their snooty heads expectantly. Aileen stamped her heel and there was a rough scuffle around the catflap as all five fought to exit first. ‘Wait till the good doctor deals with you,’ she screamed.

Cousin John said, ‘Fred Pinder over on the mainland has a stables. Supplies horses to them movies that come venturing up round here. He can get you a whole bloody cavalry troop. He’ll bring you over a unicorn in his horse box.’

Sullivan never passed a penny on a pavement without picking it up. He had been Sussex-born and bred. He owned this long playing record, Old Songs of Sussex: Agricultural Labourers’ Ballads From Both Sides of the Downs. I loved that: “Both Sides.” I wanted to ask the doc if I could inherit the disc.

In the seventies and eighties, Sullivan had made his money from slot machines in Brighton and Eastbourne. One time I asked him what it was like as a livelihood. “Brighton Rock meets parking meters, ’was all I got.

Aileen once told me that Sullivan collected the coins in straining plastic buckets every night of the week and loaded them into his Volvo hatchback. The rear suspension broke. Apparently there were one hundred and fifty unused mops in Sullivan’s Brighton garage.

A What the Butler Saw machine still stood in the front lounge at ten pence a go. I’d have loved to have inherited that too, but the doc had got the house contents as well in a later poker game.

Sullivan had fallen in love with Mull after just one drive around it. He must have seen Calgary Bay for the first time that very day. I never once heard of him going round the island again, so it made an impression.

Above Tobermory, Sullivan’s fine view over the bay and across the Sound of Mull, our poker evenings and those few winning dinners at the Western Isles Hotel seemed enough.

I once asked Sullivan why he loved it up on the island so much and he swung open all the bay windows. ‘Listen,’ he yelled. ‘Just silence, isn’t it? It’s the elsewhere. When you’re an Englishman you have England and you have…elsewhere. And you have to pay to get elsewhere, sonny boy.’

That first winter of westerly gales, silence was in short supply. The poker games were interrupted affairs. The tiles rattled on Sullivan’s roof like a miked-up marimba. We watched the molehills actually slide across his lawn and up the slope where they tipped into his fish pond. The herons had taken all the goldfish. On the third day of gales, a baffled young thrush came down the chimney and immediately broke its neck on the inside window pane. Sullivan took it to the kitchen and de-suctioned the backdoor open: that dead bird flew one last time, off the end of the shovel and heading east, at sixty miles an hour.

Plumpton’s lock-less catflap had been going mental, like the chattering teeth of some giant. It had to be sealed with electrical tape which puffed and salivated. Sullivan didn’t venture up for many winters after that.

When I returned to the isle one week after our meeting at the police station, I was not alone in the bar of the car ferry.

Fred Pinder had often phoned from his stables and sensibly suggested stunt women from the film industry. Portraits had been e-mailed to Cousin John. But none of these women passed his strict criterion.

There I was on that early boat with Fred Pinder in his vintage SNP t-shirt. And with Miss Zoë Murphy, a third year Dramatic Arts student from Coatbridge. Coatbridge Sunnyside, she emphasised.

Zoë had told me she wanted to be in musicals but this assignment seemed like a strange first step. We paid her seven hundred cash upfront, but she still insisted she’d throw in some pole dancing, of which she’d done plenty to supplement her student grant.

Every person in the ferry’s bar stared at Zoë in her fluffy blue, fake fur jacket – even the women. I believed someone was going to approach her for an autograph.

When the vessel came into the Firth of Lorn, spray smashed the bar windows like shampoo suds on a shower cubicle and the boat dipped from bow to stern. After ten minutes Zoë headed for the toilets.

Fred Pinder was drinking whisky with Irn Bru and he leaned across. ‘I’m away down to see if they’ll let me check Blade isn’t kicking the back of his box out.’

‘I don’t think she can ride. Can we sit her on the horse in the box first, for a wee try out?’

Fred said, ‘No. You pay me for the horse. I’m nothing to do with any rider.’

After Fred had gone, bare-footed Zoë swayed back to my table. She’d taken off her heels and carried them by the straps in one hand. The make-up and the tanning salon were all in vain up against the tossing Firth. Her beautiful young face was grey as steak.

‘Look. I know you swore you could, but you’re not like all those other actresses, are you? Water-ski, snowboard, speak Polish, ride a motorcycle and horse?’

‘Ah can ski. I’ve been to Chamonix.’

‘Horses though. Sure you can…canter a horse, hands-free in a force ten? Even a wee trot maybe?’

‘I’ve a nice bikini. Did plenty gymkhana when I was wee; rosettes all over my bedroom wall in Coatbridge. Sunnyside. We’re no gonna sink are we? Has this boat sunk before?’ She looked fearfully around the panorama. ‘Look at all they mountain things. We’ve mountains in North Lanarkshire too. I climbed one when I was a wee lassie.’

‘Really? What one?’

‘One of they slag heaps from the old coal mines.’

She soon returned to the toilet with her arms held out horizontally. She’d left her high heels upright on the table and they fell to their sides and spilled my coffee.

Word travels fast on the dark island. At the ferry terminal, five boy racer cars were drawn up broodily in their usual row. Observing exactly who disembarked. I noted the car windows were all open; the young male drivers and passengers shouted excitedly through those aligned windows, like some antiquated telegraph system.

Those five cars followed my hire car and Fred, towing his horse box, up the road all the way to Tob’.

Zoë had sunglasses on next to me. ‘I feel all famousy already,’ she told me. ‘I’ll just put on a wee touch more cheesy lipstick.’ She wound down her window and her shades blew off.

Around Sullivan’s ashes – in the champagne bucket sealed by clingfilm – there was a party going on up at the bungalow. All our old poker crew was there. Aileen was drunk and repeatedly played No Tears (In The End) by Roberta Flack on the hi-fi. Disturbingly though, Aileen was only dancing with Doc Fraser.

Zoë furrowed her brow at the turning vinyl and actually asked me, ‘This isnie a CD. How’s this thing make music?’

Cameron, that wannabe journalist, was there and he kept trying to interview Zoë, telling her it was for the Island Arts Newsletter. Then Cousin John arrived, already in black tie. He studied Zoë from a distance in a shy but still unhealthy manner then crossed over to me and whispered, ‘Aye. Good long fingernails there for the clingfilm.’

Zoë sneaked back to the bathroom yet again. Then she appeared next to Doc Fraser and crying Aileen.

Zoë tapped the doc on his shoulder. Johnny Cash was singing Melva’s Wine which never failed to make Aileen weep. Zoë showed the doc something and suddenly the couple broke off from dancing and the threesome headed back to the bathroom and locked the door. I became fearful that drug use had reared its ugly head – imported into our poker circle by Zoë – or perhaps practices which were even more unspeakable.

But soon the doc emerged and drew me aside from the melee. ‘That daft wee lassie you’ve got can’t ride any horses tomorrow.’

‘Why not?’

‘She’s months pregnant.’ He held up one of those white plastic testers with two blue lines. ‘She’s been spewing up then peeing on these all day with the same result. I didn’t even examine her. And I could have,’ he winked.

‘For god’s sake.’

Fred Pinder was listening and he laughed, but Cousin John didn’t take it well at all. Then there was a fearful crying scene. Aileen comforted Zoë and phone calls were made to a startled suitor in Coatbridge. Sunnyside.

Some of those boy racer cars presumptuously drew up outside. The young men with shaved heads were unable to choose between the pool table or hovering round Zoë, but when they found the doc had already confiscated all the pool balls they immediately gravitated to Zoë. When they learned of her condition they swiftly re-gravitated and fed coins into the What the Butler Saw machine.

‘Ach well, Sullivan would be happy business is still ticking over,’ Cousin John said and he nodded at the silver champagne bucket.

Another hour and Zoë was slow-dancing mournfully with one of the young bloods. And very soon they cajoled her off down the hill to the bars. What did I care? All was lost.

Meanwhile, Aileen had retired to her marital chambers with Doc Fraser, even before we threw the last of the poker crew out.

Cousin John whispered in my ear, ‘Well well. Looks like Aileen’s continued residence is assured.’

I nodded, noticing one of Zoë’s white testers, upright in an empty glass like a cocktail stick.

From my sleeping bag, at half four in the morning, I heard Zoë come back alone and go into the spare room. Yet through the wall, she mumbled several times, tantalisingly. I feared she was with Cousin John and, half in jealousy, I arose to find John – not for the first time – asleep on the pool table in his shirt and tie, escaping the draughts.

Zoë was sharing her bed with Plumpton the cat. ‘I suppose you want your money back?’ She stroked the old purr box.

‘No, dear. You get yourself a good fast pram.’

The next morning, the scandal firing around the island even reached my ears. Zoë had been unable to find a pole but had danced around an erect brush handle in the Mishnish then collected donations for her cause.

Calgary Bay is a noble location to spread your ashes. I can recommend it. Facing the infinite west, a cup of sparkling sand with jaws of rock protecting it – normally the sea glows chlorinated blue in at the rock edges, magnifying arm-thick ropes of kelp ten feet under the surface. It looks like a better place down there. That shade of blue would normally have matched the aquamarine lines on Zoë’s pregnancy tester. However, on that morning, turbulent swell was bursting forward from the sea in long and creamy rolls.

Up on the road a considerable audience had gathered, sheltering shamefully behind the windscreens of their cars, mobile phones and high definition camcorders ready.

With a long telephoto lens, old Shutters Stuart from The Port Star was lurking about for a photo to accompany his inevitable article. If Zoë had reached the saddle he’d probably have tried to sell it on to The Scottish Sun. But now he was in for a grim disappointment.

Our poker crew sheltered behind the horse box, around Mister Blade, Pinder’s beautiful white mare. The horse was saddled up, his ears flattened against the wind. Fred held him by the bridle and I was glad young Zoë couldn’t climb on; it was such a powerful-looking creature.

The sergeant, Cousin John, Zoë (with a hot water bottle under her fake fur jacket), and Doc Fraser – his arm round Aileen – all fearfully studied the impatient beast.

‘Nothing for it,’Aileen stated. ‘I’ve got my Wonderbra on, though I haven’t rid a horse in twenty year.’

Cousin John curled his nose. ‘That’s breach of contract.’

‘Don’t you listen to him, beautiful,’ Doc Fraser told her. ‘You’ll be as grand as Charlton Heston, riding up the sands in El Cid and if you take a wee tumble? Well, I’m a doctor.’

I shook my head, squinted out to sea, then walked down to the water’s edge. The sergeant then Cousin John joined me.

‘Aileen’s going to break her neck,’ the policeman assured us. ‘I really can’t allow it.’

‘Aye. It’s terrible. A Wonderbra. It’s breach of contract. She’s attractive but she’s not beautiful. Sullivan wouldn’t approve. And her smelling of the doc’s Old Spice too.’

‘Help us out Sergeant.’ I pointed far into the water, towards the mighty west.

They ignored us for a good spell then intuited a uniform and so reluctantly they came in, brought to our waving arms by the rollers. Two young men and two young women, rising out from the salt water, surfboards stuffed under their arms.

‘What’s the problem? There’s no restrictions here,’ shouted one man, wiping his mouth. He was offended as all our eyes turned directly to the young lady standing beside him in her wet suit.

Cousin John opened his mouth, ‘It’s Venus on the half-shell. Ask and ye shall receive.’

‘In the name of the law of this island, what are you wearing under that?’ the sergeant pointed.

‘I beg your ruddy pardon? I thought this was the twenty-first century.’

‘What are you wearing under that?’

The girl looked at her friends then back at the sergeant. ‘That it’s your business, just a bikini.’

Cousin John yelled, ‘Ever ridden a horse?’

She was Australian, twenty-two and tanned all over, hair bleached by open skies. She had ridden bareback horses since childhood and fifty quid clinched it.

She and Blade started at the far end of the beach and came back down along that surf line toward us, hooves smashing up puffs of spray as she leaned back in the stirrups.

Up and down the sand, out the flashing silver champagne bucket and freed from the young woman’s clutch, old Sullivan spread himself across our beautiful beach, each scatter like struggling, final heartbeats as he passed off quite gloriously into some new kind of elsewhere.

Copyright © 2010, Alan Warner. All rights reserved.

Supported through the Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund.

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections