The Future According to Luke

By James Robertson

We have commissioned a new piece of writing from fifty leading authors on the theme of 'Elsewhere' - read on for James Robertson's new story.

Luke Stands Alone was the worst prophet in the history of the Lakota people. He went into trances and when he came out of them he would say he’d seen the future. But he hadn’t, because nearly everything he prophesied had taken place days, months or years before. Even the century before the last one. He didn’t so much see the future as forget the past, then remember it again as if it were still to happen. This wasn’t something his friends Dean Liboux and Johnny Little Eagle felt they could really hold against him, but they weren’t filled with a lot of confidence when he made a prediction.

Dean and Johnny had discussed Luke’s prophetic failings often and concluded that the inside of his head was just a trailer full of junk, with a TV in the corner playing a continuous stream of old Westerns, cartoons, commercials and documentaries. Hardly any wonder he got confused. Again, they didn’t blame him for this. The insides of their own heads weren’t so different.

One time, Luke said he’d seen white soldiers tumbling upside down into an Indian village with their hats falling off. This meant a great victory was coming, he explained.

‘You mean an old-time village, with tepees and everything?’ Dean asked.

‘I guess,’ Luke said.

‘You guess?’ Dean said.

Johnny said, ‘Didn’t Sitting Bull dream something pretty much like that before Little Big Horn?’

Luke didn’t even blink. ‘Yeah, you’re right, he did. Man, how about that?’

Days went by, and weeks, and Luke wasn’t around. Then one day Dean saw him again. ‘So when is the big victory coming off?’ he demanded.

‘It already did,’ Luke said. ‘They opened the new casino, didn’t they?’

‘The Prairie Wind? What’s that got to do with anything?’

‘The first Saturday it was open, a bunch of Air Force personnel came over from Ellsworth and lost two thousand dollars at blackjack. Ain’t that a victory?’

‘I suppose you’re going to tell me they took their hats off when they came inside?’ Dean said.

‘I guess,’ Luke said.

‘But there ain’t no tepees there. They got a 78-bed hotel, but no tepees.’

‘They got tepees on the website,’ Luke said. ‘Check it out. Just like in my vision.’

Dean didn’t have a computer. He could hardly think of anyone he knew who did. He could think of quite a few who had electricity and even a land-line, but computers were thin on the ground on the reservation. Luke himself didn’t have one, so he must have seen the website some place else. He used to disappear for long periods, and when he showed up again he would make out he’d been living rough in the Badlands, on a quest for visions, but usually somebody would have spotted him in Rapid City or Sioux Falls. Once even in Denver. Maybe he’d looked at the website in Denver.

There was nothing particularly unusual about the way he took off like that: a lot of folks came and went on the reservation, many of them spent time in the cities, and visions of one kind or another weren’t uncommon either. Johnny and Dean had had visions themselves. But these days Dean was trying to avoid them. He wasn’t smoking weed or eating magic mushrooms, and although he still liked to drink he was sticking to Budweiser. He’d decided drinking vodka or any of those ten per cent malt liquors was the quickest way to death and he didn’t want to go there yet.

As for Johnny, well, Dean didn’t know what Johnny wanted. He had a girlfriend who had a baby by another man, and he seemed to like her and the kid but he didn’t spend much time with them. He preferred hanging out with his male friends, getting drunk. A lot of guys were like that, whether or not they had girlfriends. Life was difficult and drinking made it easier, at least for a while. Maybe that was what Johnny wanted, just for life to be easier. Maybe that was all anybody could want.

Johnny and Dean were good drinking buddies because neither of them was into fighting – each other or anybody else. They tried to stay away from guys they knew who got fighting drunk, because it hurt too much being punched by them and it hurt too much having to accept their apologies when they sobered up. They both liked drinking with Luke, even if he was a shit prophet, because he didn’t want to fight either. The three of them would sit around moaning about all the bad things that had already happened to the Lakota, and Luke would foretell all the bad things that were still to come.

Of course you didn’t have to be a prophet to be able to do that, you just had to walk around with your eyes and ears open. Luke could tell you, for instance, that in the next three months there would be X number of car wrecks involving Y number of Indians, and you knew that, give or take a few, his prophecy would come true. He could give you similar predictions about how many people on the reservation would die of alcohol poisoning, how many overdose, how many be murdered, how many commit suicide, how many be assaulted, how many be arrested, how many get jobs, how many lose them, how many reach the age of fifty, how many not – until at last, maybe around the fifth or sixth beer, you’d say, ‘But Luke, you ain’t saying nothing we don’t already know.’ And Luke would say, ‘Yeah, but wasn’t I right about the Little Big Horn?’ or, ‘Wasn’t I right about the casino?’ And you didn’t argue with him, you just laughed, because what else could you do? And anyway, you weren’t drinking to argue, you were drinking to get drunk.

Selling, buying or drinking alcohol was illegal on the reservation. So what Dean and Johnny would do was drive over the boundary to Jubal Schele’s place, the Buffalo Saloon, and drink there. This one day they had scraped together a few dollars – enough to put some gas in Johnny’s beat-up old car – and had set off up the road, and after a few miles they passed Luke Stands Alone walking, so they pulled over and gave him a ride.

It was a cold, clear afternoon in November. When they arrived at the Buffalo Saloon and got out of the car, Dean saw snow on the distant Black Hills. He drew this to the attention of the others. ‘Yeah, I dreamed about that,’ Luke said. ‘I saw it on the weather report,’ Johnny said.

The bar was situated on a rough old back route between Bombing Range Road and the highway to Custer, and the only reason for it being there was to serve liquor to Indians. The big old sign on the roof said INDIANS ALLOWED, which kind of proved the point, but the story was that back in the fifties the words NO DOGS OR had also been up there. Dean asked Jubal if this was true. He asked it in a friendly enough way, but Jubal looked at him suspiciously, like he was trying to start some trouble, even though they were the only customers.

‘What if it did?’ Jubal said. ‘That’s an artefact, that sign, a piece of the old days.’

‘Them old days,’ Johnny said sourly. ‘Ain’t they over, Jubal?’

‘They sure are,’ Jubal grumbled, in a way that made you understand he missed them. ‘Genuine goddamn piece of Old West memorabilia, that sign.’

‘Maybe you should try selling it on eBay,’ Johnny said.

‘Why would I do that?’ Jubal said. ‘Might want to sell the whole place some day, and that sign’s a part of it. Integral, you know? So I think I’ll leave it where it is. You boys wanting some more beers now?’

While Jubal was away Johnny said there could be no greater irony than three Lakota men of warrior age drinking liquor in a white man’s bar located midway between a town called Custer and a U.S. Air Force bombing range, and Dean said, oh yes there could, those same three Indians could be laughing about it. So they laughed about it and then Jubal came back with the beers and took the money from the pile of dirty dollar bills and quarters in the middle of the table. Jubal was happy for them to drink as much as they liked, but he didn’t keep a tab, not for Indians here in the back room. If there were ever any white customers in the front room, maybe tourists headed for Mount Rushmore, he’d have kept a tab for them, but there never were.

Dean went to the men’s room to take a leak. The walls were painted a deep brick red that was almost brown, and there were darker, menacing stains in several places. There had been an infamous fight at the Buffalo Saloon once, many years ago, before Dean was even born, between some reservation Indians and some outsiders, city Indians. Skins versus breeds. The fight had been in the bar and then somebody had followed somebody else out to the men’s room, and a gun had been pulled, and a man had been shot and killed. Just thinking about it spooked Dean a little. He seemed to recall that the man hadn’t died right there, but later, in hospital. For a while after that the Buffalo Saloon had had a bad reputation and was always busy. That was when Jubal should have sold the joint. These days it was mostly quiet. There were other places just off the reservation that you could walk to, and where you could get drunk for less – liquor stores, not bars. They were the places most people went to now.

For all that he didn’t want to fight, Dean kind of wished he’d been at Jubal’s back then. He wished something would happen. It wouldn’t matter if it was good or bad. Just if something would happen. He felt like he wasn’t fully alive, like somebody had reached in and taken some vital organ out of his body while he was sleeping. It was weird: he couldn’t remember ever not feeling like that, but he’d only recognised it in the last year. Somebody had stolen something from him, his ability to get angry or even just active. Maybe it was to do with drinking too much. Or maybe, now that he was cutting down, it was to do with not drinking enough. Hell, he was only twenty-five, maybe he’d stop altogether. If he did, would the feeling be there all the time, or would it go away forever?

Back in the bar, Luke had started to tell Johnny his latest prophecy. ‘You got to hear this,’ Johnny said. ‘Start again, Luke.’ So Luke started again.

‘I had a vision about you guys,’ he said. ‘The two of you. Only I couldn’t tell which one of you was which.’

‘I’m Johnny,’ said Dean quickly, just as Johnny said, ‘I’m Dean.’

‘In the vision,’ Luke said. ‘I couldn’t tell in the vision. Do you want to hear it or not?’

They wanted to hear it.

‘You’re standing on a road. A straight road heading right across the prairie. And a pick-up comes by and pulls over. The driver is a big white man. He’s wearing a white hat and there’s a rifle slung along the back of the cab. He offers one of you a ride, I don’t know which, and I’m saying, no, no, don’t get in.’

‘What were you doing there?’ Dean asked.

‘I was there but I kind of wasn’t, know what I mean? And I’m shouting at you not to get in the pick-up but you don’t hear me.’

‘So do I get in?’ Johnny said.

‘What about me?’ Dean said. ‘Do I?’ Because they still weren’t taking Luke seriously.

‘Neither of you gets in. First he offers you a ride. Then he offers you a blanket. I’m shouting, don’t take the blanket, it’s full of smallpox. Then he offers you a bottle of whisky. I’m shouting, don’t take the whisky, it’ll poison you.’

‘And what are we doing, just standing around while this guy offers us things?’ Johnny said.

‘Pretty much. It’s like I said, I couldn’t see which one of you he was talking to. The other one was facing away from the pick-up, looking out on the prairie. Like he was waiting for something else.’

‘For what?’ Johnny said.

‘Wait and I’ll tell you,’ Luke said. ‘The white guy offers you a piece of paper with a lot of writing on it. He offers you a kettle. He offers you a gun. It’s like he has all this stuff on the seat and he keeps showing it to you. A pair of jeans, a TV set, a cell phone. And every time he picks up something new I’m shouting, don’t take it, don’t get in the truck, let him drive away.’

‘I’d take the cell phone and the jeans,’ Dean said.

‘I’d take the gun,’ Johnny said. ‘I’d blow the asshole’s brains out and then I’d get everything.’

‘Don’t take the gun!’ Luke shouted suddenly.

From out front they heard Jubal’s voice. ‘Hey! Cool it back there.’

‘Whatever you do, don’t take the gun,’ Luke said, lowering his voice. He was out in a sweat, and shivering, like he had a fever. Johnny looked at Dean. Dean looked at Johnny. ‘It’s okay, bud,’ Johnny said to Luke. ‘I ain’t going to take the gun.’

‘The other one of you,’ Luke said, ‘is still over on the roadside, waiting. And now there’s someone coming. It’s a rider on a horse. An old warrior, painted up and wearing a war bonnet and everything. But I can see right through him, like he’s made of air. He’s a ghost. And he stops his horse and looks down at you and for a long time he doesn’t say anything. He doesn’t offer you anything because he ain’t got nothing to offer. And then he speaks.’

‘What does he say?’ Dean asked, after Luke hasn’t spoken for a few seconds.

‘He says a time is coming. All the ghosts are coming back. The buffalo are coming back. The deer and all the other animals are coming back.’

‘Oh man,’ Johnny said. ‘Is that it? Is that your prophecy? We had this a thousand times before.’

But Luke Stands Alone didn’t seem to hear him. The sweat poured off him, and he just kept on talking, as if he were the old ghost warrior himself. ‘The uranium is going back into the earth,’ he said. ‘The garbage is all going back to where it was made. The cars are going, and the missiles and the pollution. People don’t know how to live in harmony with the earth. The wasichus never knew how, and most Indians have forgotten or been killed for trying to remember. But a time is coming. Don’t get in the car with that old man. Don’t take any of his gifts. Just wait. Don’t forget who you are.’

Luke stopped, and for a minute nobody said anything. And then Luke wiped his face and said, ‘And he rode off across the prairie. And I looked and the road wasn’t there any more. The pick-up was gone, and so was one of you guys, but the other one was still standing, staring out at nothing.’

‘Goddamn ghosts,’ Johnny said.

Luke put his head down on the table. It didn’t take much to get him drunk, but he looked more exhausted than drunk, as if the vision had taken all his energy out of him. In a minute he was asleep.

Johnny looked at Dean. Dean shrugged. ‘Well, just because he stopped drinking don’t mean we got to,’ Johnny said, and he called on Jubal.

Jubal brought them more drink. He jerked a thumb at Luke. ‘He can’t sleep in here.’

‘Looks like he’s doing it fine,’ Johnny said.

Jubal said, ‘I’m saying he can’t sleep in here. You can take him out back and he can sleep it off in one of the cars in the yard. Five dollars for the privilege. For that he even gets a blanket.’

‘We’ll be going soon,’ Dean said. ‘Just leave him be, won’t you? We’re your best customers.’

‘We’re your only customers,’ Johnny said, ‘and we ain’t going yet.’

‘He can’t sleep in here,’ Jubal said. ‘Either you take him out to the yard, or you put him on the street, but he can’t stay there.’

‘It’s going to be a cold night,’ Dean said. ‘He might freeze. He might not wake up again.’

‘That’s why he gets a blanket,’ Jubal said.

‘Leave him till we’ve finished these beers,’ Dean said. ‘Then we’ll move him.’

Jubal retreated, muttering.

Johnny said, ‘I’m drunk. Maybe we’ll all sleep in one of Jubal’s old wrecks.’

Dean said. ‘Give me your key, man. I’ll drive. We’ll buy some more beers to take with us and we’ll get Luke in the car and we’ll drive a little ways and then we’ll pull over. We’ll have another drink and then if I can’t get you to my place we’ll all sleep in the car. That way we’ll keep warm. There’s snow coming, Johnny. We ain’t leaving Luke alone, here or anywhere.’

‘I didn’t say we would,’ Johnny said.

‘We’ll have sweeter dreams in your car than in Jubal’s yard. Indian dreams.’

Johnny put a hand on Luke’s back. ‘Do you think he’s dreaming about us now?’

Dean laughed. ‘Yeah, I think maybe he is. I think he’s looking out for us, so we got to look out for him.’

They finished up, and then they hauled Luke through the front room of the bar and out to the street, which wasn’t much of a street, just the road with the bar alongside it and a sign that said MAIN STREET. Jubal looked like he’d never seen such a thing in his life, Indians leaving the Buffalo Saloon in a state of semi-sobriety, but he didn’t try to persuade them to stay. Maybe he was as tired of it all as they were. Maybe he knew there’d be another party along soon enough.

They slung Luke in the back of Johnny’s car and Johnny gave Dean the key and went back in for a six-pack.

Luke didn’t stir.

Dean stood in the road, feeling the chill air, watching the snow-lined hills fading into the dusk. Far, far off he thought he saw the lights of an approaching car. Then he didn’t, and there was nothing but darkness gathering around him.

The door of the Buffalo Saloon slammed, and Johnny staggered over.

‘Hey, Dean,’ Johnny said. ‘You all right, man?’

‘I’m good. You all right?’

‘I got some more cans. We’re going to be fine. Hey, Dean, what do you see out there? You see something?’

Dean watched a few moments longer. The sky was clouding up. There were some stars, but they weren’t going to last.

‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘Maybe I do. What do you see?’

Johnny stood beside him, the brown bag with the cans in it under one arm. He put his other hand on Dean’s shoulder, to steady himself, and they peered into the night together for a long time, not saying anything, while, on the back seat of the car, Luke lay sleeping like a child.

Look, Listen & Read

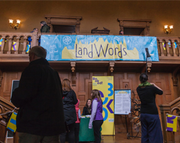

LandWords returns in May after success in April

Fri 29 April 2016

- 2026 Festival:

- 15-30 August

Latest News

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections