The Good Conduct Medal

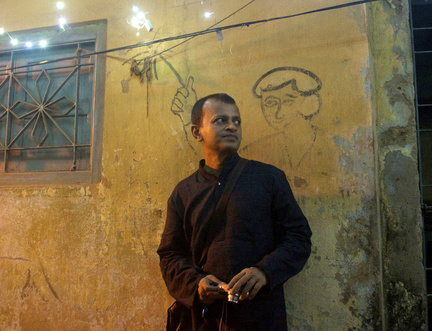

By Sandip Roy

In 2018, we commissioned 51 authors from 25 countries to write essays exploring ideas about freedom for The Freedom Papers, a publication produced in partnership with Gutter Magazine. Read on for Sandip Roy's essay, and visit guttermag.co.uk to purchase a copy of The Freedom Papers.

I was eight years old when I won a Good Conduct medal at my school in Kolkata. It went perfectly with the side parting in my hair, the handkerchief in my pocket, the black-rimmed spectacles. I was proud but did not realize it would become an albatross around my neck. Being teacher’s pet and mother’s pride was the cover behind which I tucked my gayness away, terrified that even a whiff of it would shatter the goody-goody placidity of my life. The medal soldered that vicious circle of goodness.

I went to America ostensibly to get a postgraduate degree. But I also went to be free of that Good Conduct medal. Even a small Midwestern town in the Bible Belt spelled freedom. My parents were kind, loving to a fault. I did not fear their rejection but I dreaded their disappointment. I wanted to be free to love. But I also wanted to be free from love, love that wanted to know ‘Will you be home for dinner tonight?’ and stored your medals in the bank locker, not because they were worth much but because a burglar might not know the difference. Yet the freedom to love seemed a romantic fantasy, something we had only heard about and never tasted – like an avocado or a Bellini.

In America that first taste of freedom felt exhilarating. I moved into a tiny studio apartment, an ‘efficiency’ as it was called, which I could ill afford, just to be on my own. I did not want a roommate asking where I was on a Friday night. I remember a lover surprising me at daybreak, showing up with pancake mix and strawberries to fix breakfast. At that moment freedom tasted like maple syrup on a Sunday morning.

But I had more freedom than I knew what to do with. When I called my mother we had little to talk about except whether it was cold, what I had for dinner, or which cousin was getting married. I made up stories about chicken curries I had cooked rather than confess to microwaved TV dinners. A lover broke up and no shadow of heartbreak fell on letters I sent home. I thought I was free, but really I was just off the radar of my family. Freedom was another country.

When I finally came out to my parents after moving to San Francisco my mother was shocked. My father, a soft-spoken man, took off his glasses, sighed and said ‘You are grown up now. It is your life. But will you be safe? Even in America I read about hate towards the gays.’ I felt relieved to have told them but also guilty at how anxious I was to escape back to San Francisco.

My father died while I was in San Francisco. I was watching a film that night. Dinner was warming in the oven before I checked my voicemail. I did not weep. I just felt empty. We had never spoken about my sexuality again after that first time. Now we never would. After my then partner and I bought a house in San Francisco, even as my mother boasted about it to my aunts, she asked wistfully ‘Will San Francisco now become your home for good?’

When I moved back to India, many American friends were flummoxed. Do they have gay bars in India? Why are you going back they wondered. I give different answers, none incorrect, none entirely true. I came back because my mother was growing older. I came back because I wanted to write. I came back because I wanted a change from California’s soy latte Neverland. But I also came back to learn if I could be free amidst all the ties that bind me to this place.

Will you be home for dinner tonight is still a family refrain. I’ve just learned to sometimes say no. This freedom is messily tangled up in the lives and hurts of others, some days it feels like more responsibilities than rights. Yet those responsibilities give the rights meaning.

An LGBT Pride Parade in San Francisco with its feathered drag queens, muscled go-go boys, and preppy Google employees, is always a celebration of the freedom to love. When I walk in a Rainbow Parade in Kolkata, transgender activists, their makeup running in the sun, protest the murder of a trans sex worker and young men wear masks and dance to Bollywood songs. It’s still the freedom to love but with a different urgency.

In today’s India the freedom to love feels increasingly a state subject and not just for those like me whose love is criminalized by the penal code. In 2018 the Indian Supreme Court ruled that the choice of a partner within or outside marriage was integral to the right to life and liberty. The court had to rule on this because a lower court had annulled the marriage of a Hindu woman who had converted to Islam and married a Muslim man even though she insisted she had done it of her own free will. Village councils issue diktats banning mobile phones and jeans for young women so they do not lead men into temptation. A vigilante organization went to pubs on Valentine’s Day and dragged women out by their hair.

They are all fighting for the freedom to love in ways far more perilous than mine in homes, in public spaces, in courts. Ironically, as two men together, my partner and I can often escape the scrutiny the moral police reserves for men and women. We are never asked to show a marriage licence while checking in at a hotel the way they can be. We eke out space for the freedom to love whether or not there are gay bars. It’s not perfect but freedom is not a binary, it’s a spectrum, a work always in progress.

My mother will never march in a Rainbow Pride parade in Kolkata but the other day she said ‘Invite your friend for dinner as well, all your cousins will be here’. I know my partner might be bored at that dinner but that’s ok. The freedom to love is as exciting as the responsibilities of love can be boring. A bit like a Good Conduct medal.

Copyright © 2018, Sandip Roy. All rights reserved.

Supported by the Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund through Creative Scotland.

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections