More articles Saturday 15 August 2015 7:24pm

Creative worlds of Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan discussed at Book Festival

THE creative worlds of two of literature’s greatest children’s writers, Lewis Carroll and J M Barrie, and their impact on modern culture, were discussed at the Book Festival this morning.

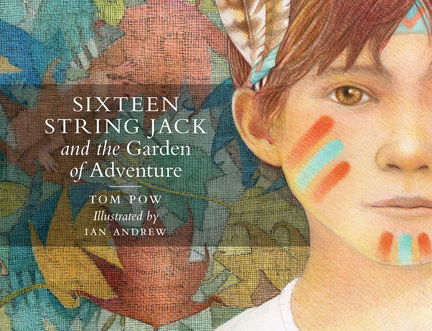

The books in the limelight were Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s The Story of Alice, which looks at the lives of Lewis Carroll, his literary muse Alice Liddell, and the 150-year-old story that she inspired, and Tom Pow’s beautifully illustrated novel, Sixteen String Jack, which investigates the childhood world of JM Barrie at Moat Brae House in Dumfries, the inspiration behind his most famous literary creation.

In setting out the lasting effect of Alice in Wonderland, Robert highlighted how Carroll’s best-known creation had become co-opted into modern culture, woven into the lyrics of The Beatles and Jefferson Airplane, turned into fairground rides at Disney World and even used to describe psychological conditions.

“Over 150 years a story about growing up has itself has developed in surprising ways, and what started off as an attempt to entertain three little girls in Victorian Oxford has become an important part of the story that we tell about ourselves,” he said. “In 1990 the New York Times ran an article about Alice under the headline, That Girl Is Everywhere. And since then, she has become even harder to pin down. If literary characters can be national treasures, then Alice definitely qualifies.”

Tom Pow told our audience that through replaying the scenes of Peter Pan with his son, invariably cast as Captain Hook, he came to understand the lasting appeal of J M Barrie’s book to children and adults.

He said the inspiration for Sixteen Strings grew out of a “sense of place and a sense of play”, referring to a visit he made to Barrie’s Dumfries home. “It was here J M Barrie played with two boys, and he later said that this was the place where Peter Pan was born,” he explained. “He [Barrie] said that, recalling the time at garden of Moat Brae House, ‘when the shades of night began to fall, certain young mathematicians shed their triangles and became pirates on a sort of odyssey that was long afterwards to become the play of Peter Pan’.”

Tom added that for Barrie, the experience of playing and observing children playing, in particular those of the Lleweyn family, had been central in his creative process. Quoting Barrie as having said that “nothing important happens after age 12”, and that “writing about a boy is the next best thing to being one”.

Tom contrasted this with what he perceived as Carroll’s approach, which he described as the author posing a series ‘what if?’ questions to himself and drawing his inspiration from them.

Discussing the effect the characters had on their real-life inspirations - Peter Lleweyn Davies, who committed suicide later in life, had struggled with his public perception as the real Pan, while Alice Liddell hid her literary incarnation for many years - the two authors agreed that the nature of the creations meant they had very different impact on their pair’s lives.

Tom said: “The thing about Alice in Wonderland is that it’s full of questions. One of the main things is ‘who am I?’ And she [Alice] can say ‘I’m an old woman’. Peter Pan is ‘I just want to be a boy and have fun’, there’s a kind of wilful determination to be stuck there.”

Robert added that when Liddell finally revealed herself as the ‘real Alice’ in 1928, then in her late-70s, she caused a media sensation, but was a “reluctant celebrity”. He said: “There is a letter in which she comes back from New York in 1932 saying is it wrong to be tired of being Alice in Wonderland? But I do get tired. So I suppose she managed to separate out her literary identity from her personal identity and saw them as two separate beings.”

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections