More articles Monday 29 August 2016 4:20pm

Mothers, Madness & Cultural Inheritance - from Morocco to Nigeria

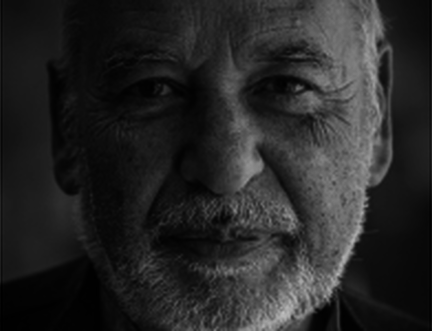

It was his mother who turned Tahar Ben Jalloun into a writer, he says – but not by reading to him or teaching him to write, for she could do neither herself. The Moroccan novelist explained in his Book Festival event that as a child watching how hard his mother and her sisters worked, and how little appreciated their efforts seemed to be, “I said to myself: one day I’m going to tell their story.”

He developed his writing whilst in a military prison for his part in student protest marches – “I was released with my pockets full of little pieces of paper” – and published a long succession of novels, respected enough that he has been shortlisted for the Nobel Prize for Literature. Only now, however, has he explicitly fulfilled his early vow, with his new book About My Mother. It tells the story of his mother’s life. Such a gesture is, he said, in keeping with his country’s approach to parenthood and old age. “In the Muslim world there is a very strong relationship with parents. You can’t rebel against them; you love them no matter what. The elderly person is respected and surrounded by family until their very last moments.” There are, he noted, “no old folks’ homes in Morocco” – families stay together.

The bonds of family, their complications and the pain of their severance are also themes for the young British/Nigerian author Irenosen Okojie, who appeared to launch her debut novel, Butterfly Fish, which skips between the London present and the Nigerian past in pursuit of plundered Benin treasures, family secrets and the inner life of a young woman named Joy. The character’s name is, Okojie acknowledged, ironic. “She’s really quite a depressed and quite a fragile character… I really wanted a character who was a mass of contradictions.” Her story emerged, she said, from her own desire to culturally connect with Benin – “I knew somewhere I would incorporate that into the story” – and to confront the experience of trauma and grief. “She’s someone who suffers from depression but is also coming to terms with her mother’s death. She deals with this grief in quite interesting and unhealthy ways…. but she also gets to know her mother all over again.”

The more experienced writer readily agreed that the darker side of life is where inspiration thrives. “Happiness is of no interest to writers,” laughed Ben Jelloun. “Writers are interested in what happens on the margins, not what’s normal. They’re interested in people’s suffering.”

Okojie expanded this: “What’s a marginalised story and what isn’t?”, and noting the importance of drawing certain subjects into the light, such as mental health. “In African cultures, there’s a real stigma, and we don’t talk about it enough.” Yet the Africanness of Okojie’s novel risked it being marginalised itself. On submitting her manuscript to publishers she often met the euphemistic response, “We’re not sure this is a story for everyone…”

Ben Jelloun noted that individualism being a less mature concept in Arab cultures than in Western ones, the idea of connecting people via literature was relatively recent, and still being developed – as, for interest, a tool against radicalisation and anti-democratic interpretations of Islam. “A novel can’t change the world,” he said, “but it can provide a window into another world, and make you realise you’re not alone.” He paused before a closing reminder to writers and readers alike: “You don’t want to take yourself too seriously, though.”

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections