More articles Thursday 16 August 2018 6:15pm

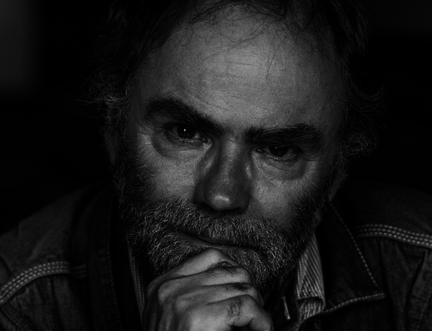

‘Quirky’ Gerry Adams ‘is political by nature’, according to unofficial biographer Malachi O'Doherty

Former Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams may have a “quite quirky sense of humour” but is “political by nature”, according to the writer and broadcaster Malachi O’Doherty. The Belfast-raised journalist was speaking today at the Book Festival on the subject of his seventh book, Gerry Adams: An Unauthorised Life.

Talking of the time a young Adams went to an IRA parade wearing the coat left behind, in a bar where Adams worked, by a Royal Ulster Constabulary officer, O’Doherty said: “It would fit with what we’re learning about the man’s quite quirky sense of humour. There is mischief about him.”

Gerry Adams should not be underestimated, however. “We have to remember that this is a man who commanded enormous respect within the IRA; who changed the direction of the IRA leadership; who essentially organised and led the IRA hunger strikes campaign; a man for whom people were willing to die.

“He is a man who was met – and respected as an equal – by people like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair,” O’Doherty said. “He did appalling things, and yet he has been seen as a man of political genius by people who would know a political genius when they meet one.”

O’Doherty believes Adams was instrumental in the Republican shift from armed insurrection to political negotiation. “There were various factors that could be weighed up. One, of course, was that [by 1993] the IRA was completely infiltrated by the [British] Intelligence Services. We now know that the head of security of the Provisional IRA, Freddie Scappaticci, was a British Army agent. In 1990, if I’d wanted to join the Provisional IRA, I would have had to get clearance from Scappaticci; that means I would have had to get clearance from the British Army. That’s an astonishing fact that nobody dwells upon significantly.

“There was also a unique political opportunity in America, with Irish Americans getting on board and Bill Clinton prepared to confront the British to some extent. There was, of course, [SDLP politician] John Hume being the connection with America and coming up with an idea, encapsulated in the word that is now most often used to describe the Troubles, the word ‘Conflict’. Then there was the brilliant idea within the peace process that issues could be solved at different strata. You could sort out relations between Britain and Ireland without Sinn Féin being part of the negotiations; you could sort out the negotiations between Sinn Féin and the Unionists without the Dublin government being part of the negotiations. It was a brilliant diplomatic construction.

“Also there was perhaps the realisation that the IRA campaign could only do one thing: it could only veto political change, it could not proscribe the direction of political change. Republicans were in the minority within the Catholic community. The majority party at the time within the Catholic community, the SDLP, was against the IRA. It was only by ending the IRA campaign that Sinn Féin could overtake the SDLP. It may well be that which was the predominant motive.

“Adams is political by nature,” O’Doherty insisted: that by 1992 either the IRA would have had to escalate their campaign to the point where they could win – “and that was an impossibility” – or “they had to stand aside and let Sinn Féin grow. I think the deciding factor was the prospect of the growth of Sinn Féin as a political party.”

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections